Prototypes are ideal for testing an idea, improving on the look and feel of a design and for getting a sense of how the market is going to respond. After all, most successful crowdfunding campaigns have started off with prototypes that brought an enthusiastic response which helped fund more development work.

But it’s at this point, when a project moves from prototype to new product introduction, that many great ideas falter. Problems may arise because the techniques used to make a prototype are different than those for mass production. Product developers need to be aware of these differences and be prepared to make engineering, forecasting and design changes accordingly. Here are some important questions to consider on your product development journey.

What Process Was Used To Make the Prototype?

Metal 3D printing and vacuum casting are great for making prototypes. Each process can be a little slow per part, but that’s not really an issue if you just want one or a few. But when scaling up to low-volume production for a new product launch, different manufacturing solutions should be considered. In the case of a vacuum cast prototype, for example, it makes sense to choose plastic injection molding for larger quantities.

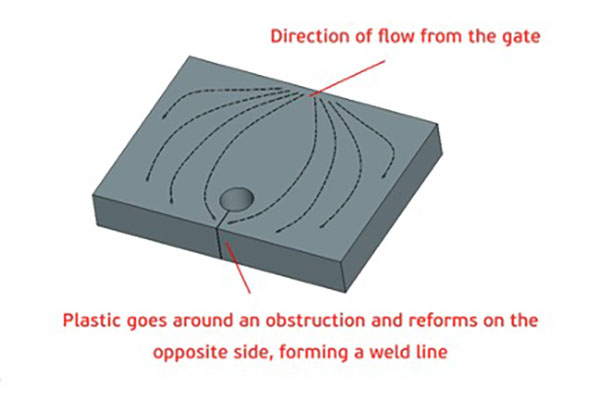

Injection molding differs from vacuum casting in many important ways, both in how the process is done as well as the results obtained. First, it requires that a hard tool be made from aluminum or steel. And injection molding rewards close adherence to design rules that don’t come into play in vacuum casting. These can include the dimensions of ribs and bosses, the use of gussets, minimal wall thicknesses, draft angles, the positions of gates, runners, ejector pins and many other considerations.

Therefore, product developers should ensure that their plans account for the additional cost and time-to-market that a transition from one process to another will involve.

Will The Results Be The Same?

A single part made by CNC machining will not be identical to a counterpart made via pressure die casting, and the differences can be both cosmetic as well as mechanical.

This is because each process introduces its own set of variables that can affect quality. For instance, die cast parts must contend with porosity, and porosity might limit the part’s strength or affect the surface finish – which is not true with a CNC machined part made out of the same raw material.

Understanding this in advance will help a product developer to calculate costs, development lead times and engineering and testing protocols for the finished part.

What Material Was Used?

Another consideration is the choice of material. A prototype, by its nature, can be made of most anything. When ramping up from prototype to new product introduction, it’s best to avoid exotic, hard-to-find, expensive or hard-to-work-with materials. The financial and time constraints of production favor the use of materials that can be purchased readily in the commercial market in sufficient quantities without supply interruption and which can be processed efficiently.

This could compromise the look and feel of the final part compared to the prototype, but this can perhaps be compensated for by using alternate finishing techniques.

What Was The Finishing Process?

A prototype that was carefully sanded, polished and hand painted with a custom color no doubt looks great. But is that practical on a large scale? Elaborate finishes tend to require a lot of attention to detail and careful hand work. This is simply not practical for volume production unless the intention is to deliberately target high-end clients. For most products on the shelf, it’s necessary to find solutions that reduce hand work to a minimum.

Processes that can be automated are one way. Another possible solution is to stick to one kind of finish rather than multiple finishes, each of which would need to be handled separately and which would represent a much larger investment in time and money.

How Many Components in the Build?

As with complex hand work, it’s also best to limit the number of individual components to a minimum for volume production. Fewer parts require less assembly, for one thing, but also represent less of a risk for breakage, loss, out-of-tolerance specifications and potential variation from one production batch to another. For volume production, minimizing every variable is the best way to both save money and maintain consistent quality.

Keep it Simple

Production places a premium on repeatability and consistency, minimizing costs, automating processes, and using simplified materials that are easily available. The engineering and design skills needed to fulfill these criteria may be different than those used to come up with the initial great idea. We are here to offer advice and alternative solutions when you upload your CAD drawings for a free quotation.